Part Two: Channelling Long-term, Flexible Private Finance into Retrofits

In our previous blog on ‘Sustainable Financing’, we established that grant funding for social housing retrofits is finite, Social Housing Providers (SHPs) have low balance sheet capacity, and existing budgets do not stretch far enough. At the same time, private funders require a risk backstop to provide confidence in their revenue floor before they can invest in decarbonisation works.

Our second blog in this series looks at how funders and SHPs overcome the above challenges to introduce a new financing source for retrofits – one that delivers off balance sheet treatment, provides a risk backstop for works, and leaves residents better off financially from day one. The way to do all this? Use an insurance guarantee to finance and collateralise the savings on the bill under a shared savings model – a process that must be underpinned by appropriate identification, quantification, allocation, and management of risk. Only then can funders invest, landlords accept the finance terms, and residents gain meaningful and guaranteed bill savings.

To understand how Social Housing Providers leverage such a scalable, standardised financing mechanism, read the blog below!

Funding Retrofits Using Future Bill Savings

Financing the savings on the bill is a well understood concept and is frequently the only viable way to fill the funding gap. It enables retrofits to pay for themselves, with future energy bill savings covering the cost of the works. But frequently, residents get the raw end of the deal, with all the savings swallowed up by the finance repayments. This is partially because retrofit savings are generally thin and partially because the upfront cost of projects and the cost of capital is high. Where this happens, the core social purpose of retrofits is undermined, with residents continuing to pay high energy bills.

Residents Bear the Cost of Inaction

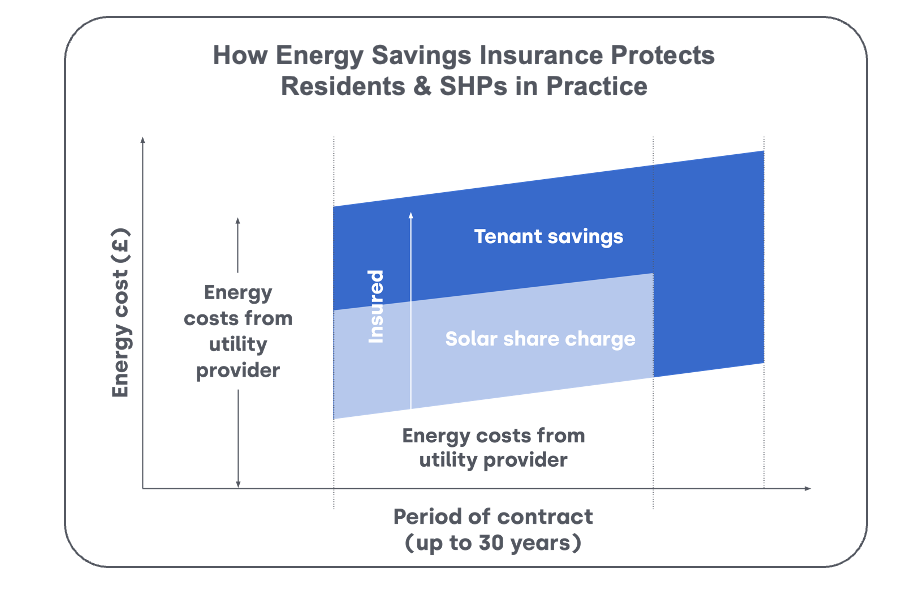

Residents have been bearing the cost of energy inefficient stock for years. Homes rated F and G are seeing bills of £4,500 a year compared to those in A-C properties on £1,800. Where providers are unable to retrofit their stock or where all of the energy bill savings are used to finance the works, energy unaffordability only gets worse. As such, embracing a shared savings model – where some energy bill savings are used to pay project costs and some are left with residents – is critical. Without this mechanism, residents will continue to pay inflated bills they can’t afford with no protection from rising energy prices, while landlords will be unable to finance their legally mandated net zero projects.

Making a Shared Savings Model Work

In light of the above, SHPs and funders need to pivot towards a shared savings model. For funders to agree to this though, they need to be able to confidently ascribe financial outputs to projects in the design stage, pre-completion. This is particularly important as a shared savings model leaves funders more exposed to shortfall as they have less headroom in which to recover their costs – an untenable position.

There is a practical element to the above. To attach a shared savings financing model to fabric measures, detailed metering and monitoring pre-project is required to create an accurate and bespoke energy baseline for each home. This baseline becomes the contractual reference point to calculate the savings for the funder, landlord, and resident. However, such pre-project metering and monitoring requirements are not the case for solar and storage measures, as these technologies produce well documented income streams which can be detached from individual households’ behaviour. Here, surplus capacity can be exported to other residents or back to the grid, achieving a financeable income stream.

So, if solar and storage technologies are done as a first phase alongside metering and monitoring, they enable and simplify the implementation of fabric measures a year or two down the line, while achieving positive buy-in from residents for the full, phased net zero pathway.

How Software Supports a Shared Savings Model

Software is a key enabler in determining whether a project’s cash flows (i.e., the savings) are large enough to both service the private finance and leave residents better off financially. It showcases early on how much a project will cost, the energy bill savings it will deliver, and the payback time.

But to get funders to lend against predicted future savings, those cash flows must be watertight. And this relies on two things: mitigating technical risk and having a savings’ recovery mechanism.

Getting Funders on Board by Showcasing the Opportunity

To get funders on board, SHPs need to profile a project’s risk of underperformance. Software can be used here to analyse a range of possible retrofit scenarios, undertake tens of thousands of scenario simulations, and map their outputs’ likelihood and magnitude of underperformance. Model outputs can account for a shared savings model and showcase different cash flows, payback time, and amount of capital required – both at a single technology system level as well as across a whole portfolio. The amount of bill savings left with residents is flexible and is dependent on several factors, including technologies’ payback time and the size of a landlord’s equity or grant contribution. However, Tallarna’s model can leave and guarantee between 20-50% of the savings with residents from day one.

For funders, such software-led risk quantification demonstrates both the scale of their investment opportunity and profiles the underlying security value at risk, informing credit underwriting. Funders now know what their returns could look like, and the risk associated with them. The next stage in getting funders on board is mitigating this financial risk and guaranteeing their returns. The way to do this? Insurance.

Insurance Underpins a New Financing Source

Insurance transfers performance risk to an insurer and turns retrofits into attractive financial assets. It does this by putting a financial contract behind a project’s kWh and £ savings – formally monetising project value streams. Not only does this mitigate risk but it creates a standardised and scalable mechanism for capital deployment. It does this by setting down consistent parameters against which retrofit income streams are delivered and valued. So, once a funder has undertaken due diligence on the insurance policy as a whole – a process they need to do only once – all projects submitted through that policy are understood entities that they can back.

This tried and tested principle of using insurance to scale retrofit investment has met with success in the commercial real estate sector.

Energy Savings Insurance Enables Long-term, Flexible Finance

Energy Savings Insurance (ESI) is a policy that has been specifically designed by Tallarna for the social housing sector to fulfil the above purposes. It backs retrofits’ technical and consequential risk – meaning that should a project’s realised energy savings be lower than predicted, the insurer will pay the difference to both residents and the funder. The insurer will also cover the repair and replacement costs of underperforming technology. This is facilitated by real-time metering and monitoring of homes’ post-retrofit as provided by Sero, which enables immediate fault detection and remediation, while facilitating data-led claims – meaning settlement without loss adjustment.

From a funder’s perspective, ESI provides a form of collateral outside of SHPs’ balance sheets and provides a key building block to enable funders to invest in a third-party financial structure. Crucially, ESI can guarantee project performance for up to 30 years – unlocking long-maturity private finance, a necessity given how thin the bill savings can be. This empowers deeper works with longer payback times – maximising the environmental and resident impact.

How Energy Savings Insurance Puts Projects Off Balance Sheet

From a SHP’s perspective, ESI enables four key things:

1. It unlocks separate ownership of the retrofit assets, meaning projects can be delivered ‘as-a-Service’.

Here, the legal responsibility for the monthly reduction in energy usage becomes the responsibility of the separate owner, not the SHP. This separate owner is called a Project Vehicle (PV), a company created to own and run a given retrofit project and which is the holder of the insurance. Funders are willing to invest in Project Vehicle – a third-party financial structure – as the insurance provides a risk backstop.

2. It removes project risk and liability from SHPs and their residents.

Project risk and liability is transferred to the Project Vehicle and mitigated by the ESI policy. This puts projects off balance sheet for landlords.

3. It lowers the cost of capital and increases the loan-to-cost.

ESI proves to investors that project income streams are predictable, long-term, and sustainable. In other words, it increases the quality of energy saving and generation income streams. Investor confidence in project returns reduces the cost of capital and enables a higher loan-to-cost. This mitigates the amount of landlord contribution, dissipating their capital expenses and/or offers the possibility for deeper savings for residents.

4. It improves landlords’ financial headroom in their existing loan covenants.

It does this by externalising major decarbonisation capital expenditure and reactive maintenance costs which lowers SHPs’ operating expenses according to their covenant definitions; uplifting resident affordability by lowering energy bills which decreases the risk of rent arrears; and helping landlords’ stock achieve EPC compliance which defends the value of their buildings.

All of the above encourages projects that are larger scale with deeper measures – meaning greater resident impact. It also frees up more landlord funding for new build projects. In fact, this same process of guaranteeing energy performance to unlock finance is applicable to new builds as well as retrofits – and will be discussed in a future blog post!

The Missing Piece in the Above? A Savings Recovery Platform

As we’ve seen above, there are two key mechanisms to getting private finance to work for all stakeholders:

1. The use of software in quantifying the technoeconomic feasibility of a shared savings model.

2. Insurance-backed guarantees that protect cash flows for funders and residents while facilitating off balance sheet treatment for Social Housing Providers.

In our final blog on this topic, we’ll be exploring how to recover the savings to service the private capital and how to maximise residents’ savings on an ongoing basis.

Authors

Tim Meanock, CEO, Tallarna

Tim Meanock is the Chief Executive Office of Tallarna. He co-founded the company in 2017 with a focus on addressing the funding gap in building decarbonisation. Tim was previously a senior executive in a high growth technology company in the video and analytics space, and prior to that spent nine years in mid-market private equity with a focus on the real estate sector.

James Williams, CEO, Sero

James is a founder and the CEO of Sero. Sero is a BCorp, that works across homes, energy, and finance, combining net zero expertise with data driven technology, to bring affordable and sustainable solutions, at scale to housing providers and residents.