How to Tackle the UK’s Broken Energy System

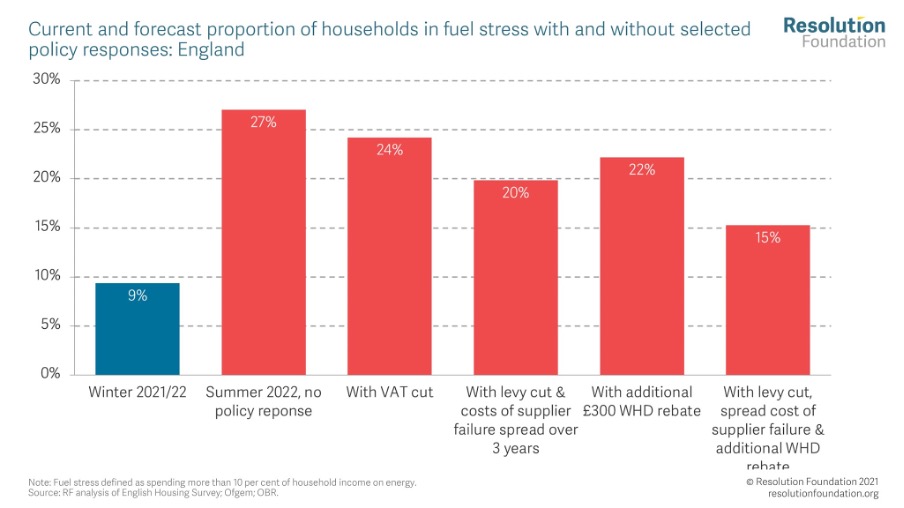

As of April, British residents could face energy bills of £1,971 a year, a potential increase of £693. Millions of working families will likely be thrown into fuel poverty, and the government’s support package of up to £350 per household offers cold comfort. But while attention is focused on the staggering 54% price cap rise, a more insidious problem lurks. And that is the substandard condition of British homes.

The UK has some of the worst performing homes in Europe. Two thirds of homes in England have an EPC rating of D or lower – resulting in energy bills double that of homes rated EPC A. Poor insulation across the country is allowing heat to escape through the walls, windows, roof, and even the floor, making warm homes a never-ending challenge. And the price cap rise will disproportionately affect homes with the poorest energy efficiency – and often, society’s most vulnerable.

Our national heating system is broken. Without urgent action, the UK will be stuck in an endless cycle of unaffordable energy bills and cold houses. But large-scale retrofits offer hope, powering affordable warmth in thousands of homes at a time. The social housing sector is where the greatest impact can be felt – and indeed where there is the greatest need.

Why are British social homes so poorly insulated?

89% of local authority housing stock was built between 1945-1980 as part of the post-war effort to rebuild Britain. But regulation on energy efficiency was sorely lacking. It was only in 1965 that new homes were set certain heat loss standards; even then, implementation was subpar. Although we now understand how to efficiently create heat and keep rooms warm, the necessary improvements haven’t always followed through. As a result, hundreds of thousands of people are living in unsustainable housing.

Many social homes from this era have unfilled or half-filled cavity walls and lack adequate loft insulation. But if housing associations are to lower resident fuel bills and protect them from surging living costs, delivering adequate building insulation will be key.

Insulation in the home is like the difference between putting your hot tea in a thermos flask vs a takeaway coffee cup. The temperature of the tea to start with is the same in both cases but one will still be warm two hours later while the other will be undrinkable. In the same way, two social housing properties may use the exact same amount of energy to try and heat their homes but the one without insulation will struggle to keep rooms warm after switching the heating off while the one with insulation will be cosy a few hours later.

Materials such as mineral wool fibre and treated cellulose have proven effective at insulating homes. They can be put into cavity walls and in lofts to trap pockets of warm air. This has been shown to be highly effective in in cutting bills, with the Energy Savings Trust estimating insulation can result in bill reductions of £380 a year.

Looking to improve home insulation as the first port of call is known as a fabric-first approach. It means maximising the performance of a building and its ability to retain heat as the priority. This is important as 60% of the energy a home uses is for heating.

What are the benefits of retrofits for residents and housing associations?

At Tallarna, we’ve seen that retrofits can reduce energy bills by 60%. At the new price cap, this equates to bills of £1,971 being cut to £788 – a considerable difference that goes a long way to alleviating fuel poverty. And the more properties retrofitted, the more residents that benefit. Social housing providers have a unique opportunity to power large-scale social change that improves residents’ comfort and creates warm homes that they can afford to heat.

But the benefits of retrofits go much further, for residents and housing associations alike. Better insulated homes have been shown to improve air quality, reduce the likelihood of damp, and even boost mental and physical health. For housing associations, higher quality homes mean fewer repairs, increasing Net Operating Income, avoiding the brown discount, and resulting in Net Present Value uplift.

Retrofits have a knock-on effort on society too. More than 130,000 jobs could be created in the next decade through the retrofit industry, stimulating the local economy and supporting regional innovation hubs.

Why is retrofit uptake in social housing so limited?

While much work has been carried out exploring retrofit options across housing associations’ stock, poor balance sheet capacity and constrained budgets have held many back from execution. Current estimates put retrofitting social housing at £104 billion. Government funding so far will cover £3.8 billion. At the same time, housing providers must ensure all their homes have an EPC rating of C by 2035.

This leaves housing associations in a double bind: insufficient government funding coupled with a legislative requirement to improve the energy efficiency of their stock. Some have turned to private funding, but overall, this has proved insufficient and expensive.

What many housing associations don’t realise is that there are significant pools of private ESG infrastructure funding that can be deployed into this space – without interfering with existing borrowing. But to access this funding route in an ethical and sustainable manner, a new approach to retrofits is needed.

How does a decarbonisation ecosystem accelerate retrofit uptake?

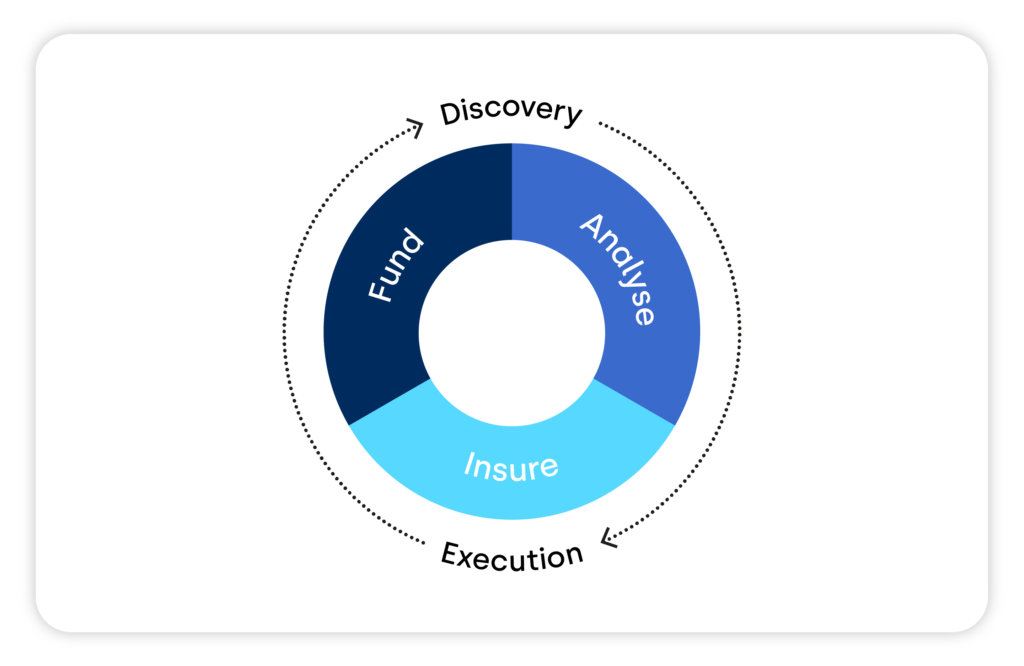

Too often, retrofits take place in a vacuum, with the worlds of building engineering, insurance, finance, and procurement working in siloes. A poor understanding of each counterparty’s views results in differing solutions to the same problem. And so, plans become confused and projects a shot in the dark.

To address this challenge, a decarbonisation ecosystem is needed. This is where connections are formed between stakeholders in the retrofit planning process and their insights are channelled through one platform. But to get to unanimous project suggestions, the risk of project underperformance must be quantified.

Risk quantification enables mitigation through insurance, verifying predicted energy savings and aligning what building engineers think is the best retrofit option with what investors think is financially viable. Forecasted energy usage reductions of 60%, EPC uplift from E to B, and bill savings of £700 look great on paper but if these outcomes don’t materialise, return on investment will be low and large-scale roll-out will be hindered – with the option of blending public and private finance shrinking.

How can housing associations access efficient funding?

Understanding the likelihood of underperformance allows projects to be tweaked to mitigate risk and improve confidence in project success. This unlocks Energy Savings Insurance where set outcomes can be guaranteed. In turn, project risk is transferred from housing associations and their residents to the insurer, resulting in off-balance finance. Efficient, third-party ESG funds can then be combined with housing associations’ existing capital, ECO funding, and grant funding to leverage sustainability budgets several times over and accelerate the scale of retrofit roll-out.

Such confidence in project outcomes provides clarity in a world of changing government legislation and stakeholder priorities. And crucially, it safeguards residents from projects that simply won’t deliver the promised results. With everyone having to carefully budget their spending in an era of rising living costs, an unexpected shortfall in energy bill savings could be the difference between eating and heating.

The case for retrofits

If the UK is to fix its devastating combination of poorly insulated homes and high energy prices, a nation-wide retrofit program must be combined with the move to renewable energy generation at the residential level. Without this, we face the stark reality of returning to a Dickensian society where the most vulnerable are subject to cold homes, insufficient food, and precarious health.

Author

Tim Meanock, CEO, Tallarna

Tim Meanock is the Chief Executive Office of Tallarna. He co-founded the company in 2017 with a focus on addressing the funding gap in building decarbonisation. Tim was previously a senior executive in a high growth technology company in the video and analytics space, and prior to that spent nine years in mid-market private equity with a focus on the real estate sector.